Henry Marsh is the author of Admissions: A Life In Brain Surgery. He is a British neurosurgeon with over 50 years of experience in medicine and has pioneered the use of the awake craniotomy as treatment for tumours such as the low-grade glioma. Marsh reveals in Admissions the haunting life of a senior neurosurgeon including first-hand accounts of poor practice, human suffering and personal confessions.

1) The mind and the brain are irrevocably linked

‘When I was younger I had simply accepted the fact that the physical matter of brains produces conscious thought and feeling. I thought the brain was something that could be explained and understood. As I have got older, I have instead come to realise we have no idea whatsoever as to how physical matters gives rise to consciousness, thought and feeling. This simple fact has filled me with an increasing sense of wonder, but I have also become troubled by the knowledge that my brain is an aging organ, just like the organs of the rest of my body. That my ‘I’ is ageing and I have no way of knowing how it might have changed.’

Perhaps the most disturbing lesson from Admissions is the reality of our entire selves being reliant on fragile flesh. Across his life as a surgeon, Marsh reveals how the very essence of our character can be augmented and dissected as tumours atler our brain matter and surgeons slice away at it. He relays a case of a patient whose marriage was destroyed by huge personality changes and outbursts of violence due to an invasive tumour and talks about his own dark tunnel toward dementia following his father. All the greatness and possibilities of the human race can be dissipate at the click of fingers if the brain is seriously damaged.

‘The physical nature of our thought, the incomprehensible unity of mind and brain, is no longer an awe-inspiring miracle but instead a cruel and obscene joke.’

2) This makes belief in an afterlife difficult

‘My understanding of neuroscience means that I am deprived of the consolation of belief in any kind of life after death and of the restoration of what I have lost as my brain shrinks with age. I know that some neurosurgeons believe in souls and afterlife, but this seems to me to be the same cognitive dissonance as the hope the dying have that they will yet live.’

One of the hardest realities of having Marsh’s experience is moving toward death without the comfort of religion. He talks of cognitive dissonance as an evolutionary psychological tactic to aid survival – the dissonance from encroaching death akin to the fierce will to live, and dissonance from seeing the fragile brain and believing in the immortal soul as another area of advantageous self-deception. For Marsh, death is absolute – not only total death, but the slow aging of the brain. As we age, our brain loses its brilliance and capacities of youth. Once we’ve lost them, we can never get them back; neither can we even remember what it was like to have them, or recall any other version of ourselves than the one we will in now. Our self from yesterday, or ten years ago, is lost forever.

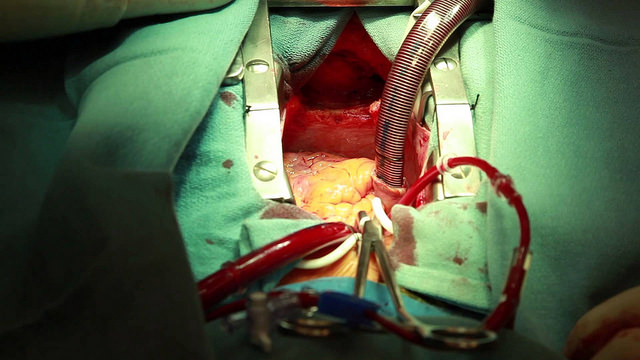

3) Death is often kinder – but that isn’t a decision you can necessarily make

‘Bitter experience of similar cases to Mr Williams’ told me that the best outcome for this man would be if the operation killed him – but I felt unable to let that happen. I knew of surgeons in the distant past who would have done just that, but we live in a different world now. At moments like this I hate my work.’

The sheer terror of having a severe brain injury is that you cannot make decisions about your own future. If you are unconscious or semi-conscious your family will make your decision for you – and often, they cannot bear to let you go, even if surviving means life on a ventilator in a vegetative state. Here lies Marsh’s tale of the evils of competitive modern medicine. As a surgeon, if you refuse to operate there will always be someone who will simply for profit and regardless of moral consequences. This could result in bad reviews, a resulting lack of patients, and your clinic closing down. Your hand is therefore forced – you are forced to create a living vegetable for families to be burdened with without much help, especially as in places without universal healthcare there will be little provided to help such families. Medicine to heal and medicine for profit is a fine tight-rope all doctors must walk on – however, with competing private hospitals and a culture of over-treatment, Marsh argues it is hard to stay balanced.

‘The evidence base and justification for each (spinal implant) surgery, at least for back pain, are very weak…spinal implant surgery is major surgery and a six-million-dollar-a-year business in the US. It is a prime example of ‘over-treatment’ that is a growing problem in modern health care’

4) Invasive tumours are deadlier than external tumours

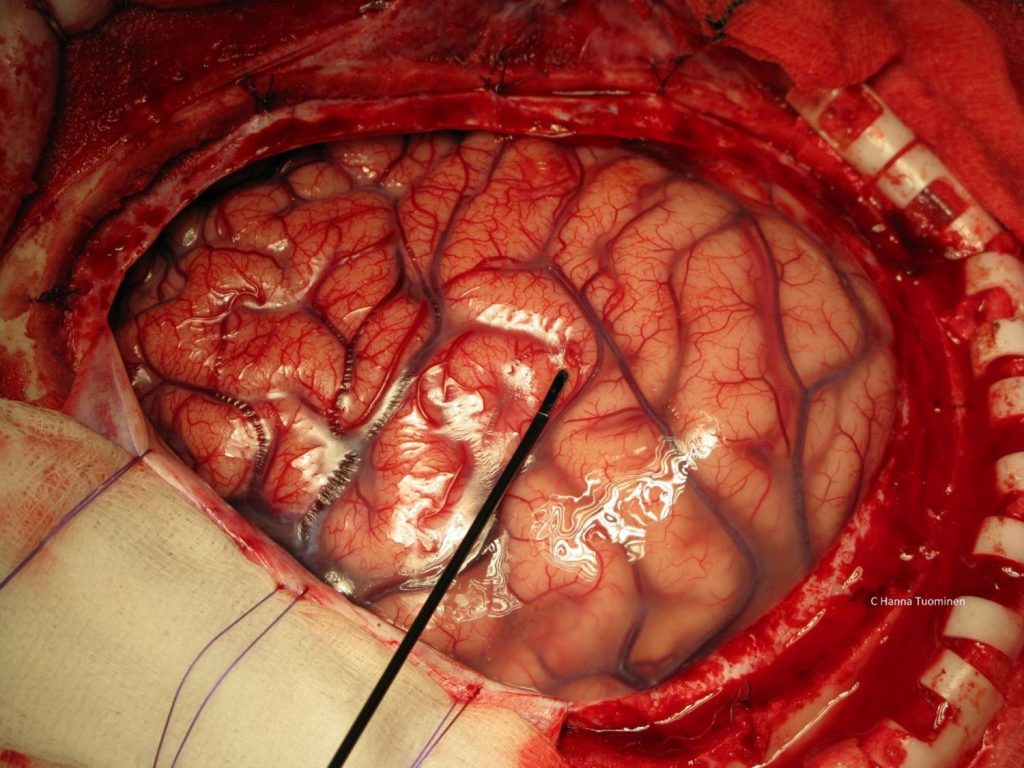

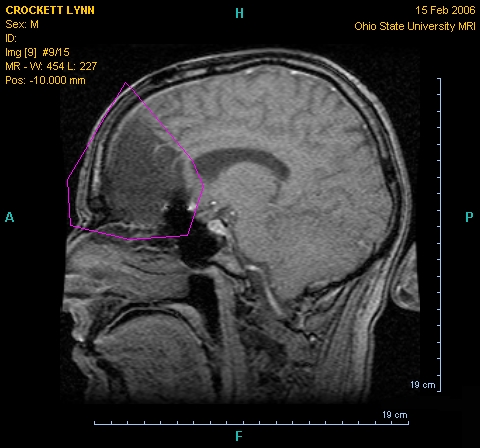

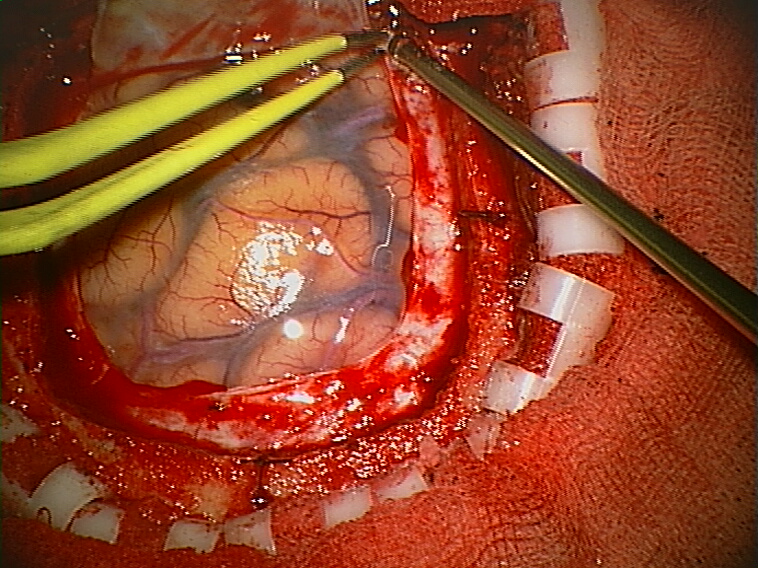

‘Tumours like this grow into the brain instead of displacing it, the tumour cells pushing into the brain’s soft substance, weaving their way between the nerve fibres and the brain cells of grey matter. The brain can go on working for a while even though the tumour cells are boring into it like deathwatch beetles in a timber building, but eventually, just as the building must collapse, so must the brain.’

One silver lining to Marsh’s book is that you learn that some famously intimidating tumours can be benign. The huge golf-ball tumour that appears on brain scans in TV serials and films is often not the short straw in the realm of brain tumours. These tumours are mostly external to the brain which essentially sit on it and decompress it – they displace the brain, which can cause death from excess pressure. These however can be removed and the patient can make a full recovery. The tumour to fear is one that will appear on a scan like a dark smudge. This is invasive and may alter everything from your personality to your vital senses before killing you. These tumours are therefore much harder to treat, and removal involves careful manoeuvring around critical brain tissue. Marsh’s accounts of these surgeries are often harrowing.

5) All doctors are novices once – and you might be the guinea pig

‘I can remember two cases – both young women – from the early years of my career where my inexperience made me too timid and I failed to remove enough tumour. They both died from post-operative brain swelling within twenty-four hours.’

The most terrifying truth of Admissions is that some must risk die so that others may live. Surgeons are mortal and will also one day perish – they must create a new generation to take on the patients they leave behind. But doctors are not born qualified, and Marsh talks about the horror of having to put patients at risk by allowing an inexperienced junior to operate. He himself was a junior once, and patients died from his inexperience – the tragic quality of surgery, he recounts, being that one learns far more from failure than success. The death of a patient due to incompetency will instruct far more than a hundred successful operations. For those who cannot afford private healthcare, we cannot choose our surgeon – we may be the necessary guinea pig for an inexperienced surgeon to learn how to operate.

6) ‘Doctors deal in probabilities, not certainties’

‘Sometimes, if you are to make a right decision, you have to accept that you might be wrong. You may lose one patient with a good outcome but you will save a far greater number – and their families – from great suffering. It’s a difficult truth that even now I find hard to accept.’

It is a sad truth that some, who could have made a good recovery and led successful lives, will die due to statistics. If it is likely you will become brain dead, you will probably be considered as such regardless of the margin of possibility that you are not. Marsh finds this fact a hard one with which to reconcile – some must die unjustly so that the many who would just suffer can die peacefully. It is essentially a practical use of utilitarianism, meaning some will be left out. Marsh mourns for those in his career that might have lived, with their families suffering so much loss.

Henry Marsh’s Admissions: A Life in Brain Surgery can be purchased from any major book retailer.