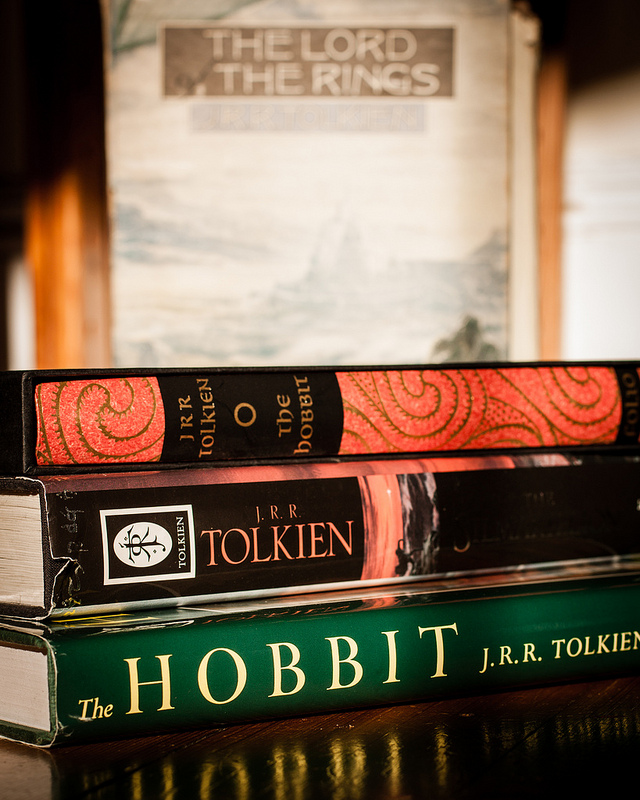

The Hobbit, too overshadowed by The Lord of the Rings?

The Hobbit, or There and Back Again is one of my favourite books. It may be a story written for children, but like the Lord of the Rings trilogy, it brilliantly demonstrates J. R. R. Tolkien’s extraordinary, boundless, imagination. He created a world with which most of us are now familiar, thanks in part to Peter Jackson’s film adaptations. ‘Middle-Earth’, ‘hobbit’, ‘you shall not pass’ and ‘One does not simply walk into Mordor’, are all phrases that are now commonly recognised, the latter immortalised by that Boromir meme which is still circulating Facebook, Tumblr and Buzzfeed even now.

One of my favourite things about The Hobbit is, like anyone else from a rural English county with a name ending ‘–shire’, I like to believe that the Shire is based on the place where I live: Shropshire. There may actually be some truth in this since there is speculation that one of the Shropshire hills, the indeed very solitary ‘Wrekin’ was the inspiration for the Lonely Mountain. Also, having ventured to some of the more rural towns in my area, I can report that some of the inhabitants are what could be considered suspiciously short. You heard it here first.

The point of that paragraph, other than to show off, is to bring the setting of The Hobbit to the foreground. Much of the Shire, featured at the start of the book, is a tribute to the ‘Merry England’ conceit of the pre-Industrial Revolution era. The rolling hills and green pastures of this utopian England are brought to life in the idyllic lives of the hobbits, rudely interrupted by a knock on Bilbo’s door one fateful evening. Tolkien seems to look back on this era yearningly, viewing the industrialisation of England in a manner akin to William Blake’s judgment of ‘dark satanic mills’. It can’t be stated enough how it is always the enemy, in both The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, who desecrate nature, and are associated with darkness and incessant repetitive noise.

The Hobbit, as you might well expect from an Oxford University professor like Tolkien, is fantastically well written. It is engaging right from the first page, and nigh on impossible to put down (I’m warning you now). The first line is as follows: ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.’ A simple start, one might say, but, if you don’t know already, you’re immediately itching to find out what a ‘hobbit’ is and why it lives in a hole in the ground. The narrative continues in this fairly simple manner, making the novel highly readable for people of all ages.

The protagonist, hobbit Bilbo Baggins is an instantly likeable character. He doesn’t seem particularly heroic at first, isn’t exactly enamoured with the thought of spontaneous adventures, and seems to be permanently focused on the pleasure of his next meal. The book is as much about the journey of Bilbo’s development in character, as it is of his literal journey, and could be seen as a form of bildungsroman, though Bilbo is rather older than the usual protagonist in this genre. Tolkien winds us through the wondrous realm of Middle-Earth as Bilbo joins thirteen dwarves and one famous wizard (no, not Dumbledore) on a quest to recover a kingdom and a vast hoard of treasure from the ferocious dragon Smaug.

Tolkien’s imagination takes the reader on Bilbo’s extraordinary adventure, encountering dwarfs, wizards, man-eating trolls, elves, goblins, orcs, wargs, giant, talking eagles, shape-shifters, giant spiders, more elves, dragons, and the occasional human, in roughly that order. A few of these creatures might sound familiar from other mythologies and legends, but many have undergone Tolkien’s own particular re-brand. Dwarves are less the cutesy, miner types that we see in Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and are instead skilled smiths and fearsome warriors. Elves are not your average undersized, slightly mischievous creatures, but are instead tall, beautiful, ethereal beings, taking inspiration from the Icelandic Alfar. ‘Warg’ is simply the Old Norse word for ‘wolf’, but even these creatures are adapted to become a mode of transport.

However, the ‘orc’ is a creature entirely of Tolkien’s own making, although grotesquely altered versions of the human form have been a feature in stories for centuries. Orcs have since been widely used in the fantasy genre, in both literature and spin-offs such as games like World of Warcraft. However, this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to looking at Tolkien’s influence. The words ‘Tolkienian’ and ‘Tolkienesque’ are now recorded in the OED, such is the impact he had on the fantasy genre and on literature in general.

Reading The Hobbit is an absolute pleasure if, like me, you first tackled the long, winding narrative of The Lord of the Rings, with its seemingly endless interludes of elf songs. Although these really are rather nice poems, they seem to me to take up an unnecessary amount of pages. Granted, Tolkien was giving a nod towards Old Norse literature with its great emphasis on inserted skaldic poetry, which just emphasises his extraordinary talent even more. However, I’m still maintaining that I could just as happily read the novels without the poems, which I, in fact, usually do.

Anyone who is going to watch the film version of The Hobbit should also read the book, in Tolkien’s original form. The story is short, to the point, and very dramatic. This is what makes it so engaging, and why I don’t really understand why Peter Jackson felt the need to make not one but THREE films, from one book. Although I enjoyed the first two films, I think they have far too much extra content added in, and yet they still manage to miss out crucial parts of the book. How, I have no idea. That said, I think that without the Lord of the Rings films, far less people would be going to see The Hobbit, or even just be interested in it, so for that, I am grateful to Jackson. But now he has made the name famous worldwide, I implore you to read the book as well. It really is just truly fantastic.