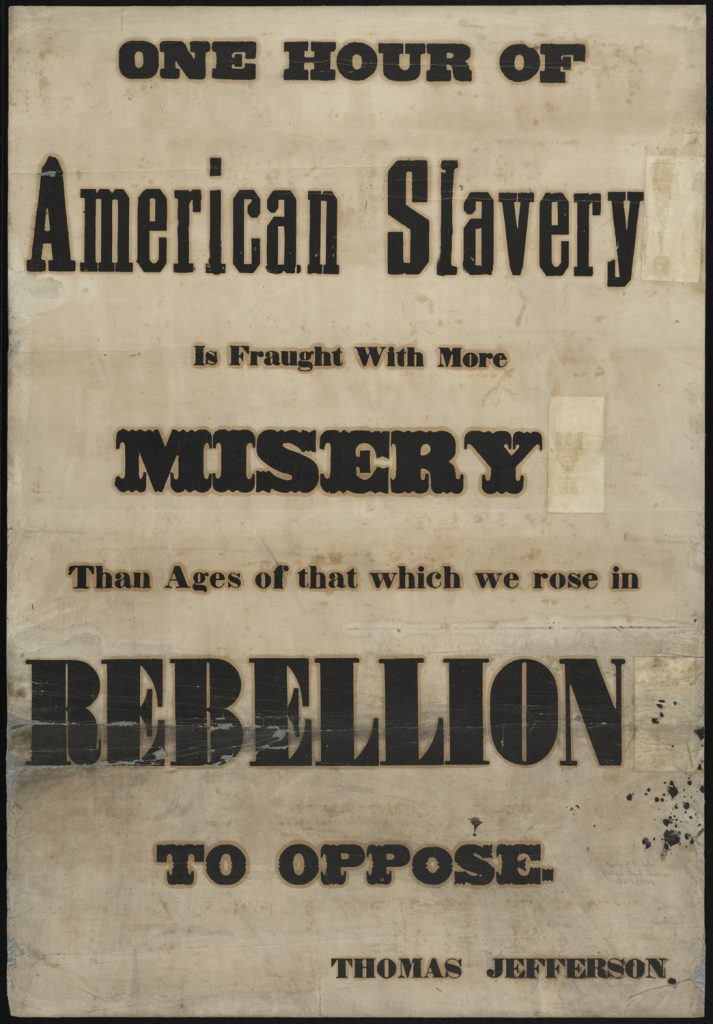

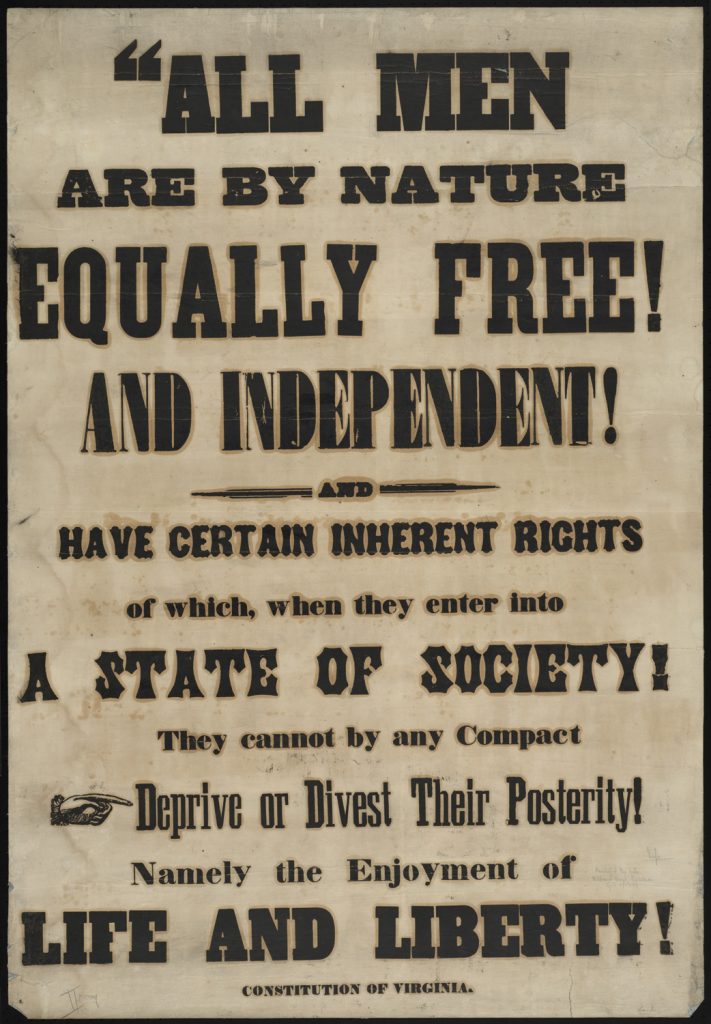

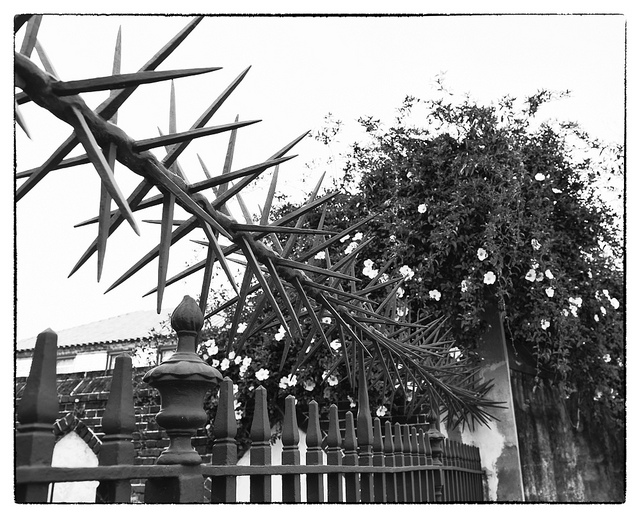

The common rebuttal from those arguing against the impact of 400 years of slavery for people of colour is the fact that slavery was a long time ago and it doesn’t affect you nowadays. That is in addition to Kanye West saying that slavery was “a choice” is an argument that is often scoffed at as the implications are still felt today such as the school of thought or the class structures that enabled such a long period of pain. Yet this is not what we are here to discuss. Instead we are tackling this statement from a scientific stance by looking at beneath the skin.

The popular Netflix series Dear White People released its second season on the 4th of May and whilst many were celebrating Star Wars Day, this social commentary which boasts an impressive 100% on Rotten Tomatoes is described as a “Netflix Original which follows a group of students of colour at Winchester University, a predominantly white Ivy League College. The students are faced with a landscape of cultural bias, social injustice, misguided activism and slippery politics. Through an absurdist lens, the series uses irony, self-depreciation, brutal honesty and humour to highlight issues that still plague today’s “post racial” society.” Whilst the nuances of an excellent series could be discussed in great lengths, it is a scene in episode 8 that we are going to focus on.

“Joelle was talking about it the other day. Sh*t. What was she saying? Oh right, it’s the inheritance of pain. Basically, scientists have figured out that people who experience intense trauma, like slavery, pass that down through their DNA, so pain and suffering is literally in my blood”

So let’s explore that. Epigenetics is defined as the study of changes in organisms caused by modification of gene expression rather than alteration of the genetic code itself. The term was coined in the 1950s in order to tell us of how genes interact with the environment and natural world in its journey to produce each phenotype. So whilst you may be born conducive to being tall and funny, being fed poorly and living in an abusive home could affect your growth and ultimately change the course of your development to otherwise. This is nothing particularly remarkable to begin with as concepts such as gene expression and plasticity have been in the biology lexicon for a long time now and has shaped the development of modern biology. Yet in order to oversee gene-environment interactions, other devices must exist and the term of epigenetics was rapidly attached to them once they were discovered, the most notable of these is methylation which is when a methyl group binds to cytosine on a stretch of DNA, and renders it less active. Yet the question of environmental factors affecting the next generation has long since been around, Jean-Baptiste Larmarck argued that characteristics that were picked up could be passed on whilst even Darwin thought that this could be the case, thinking that lifetime experiences could spawn “gemmules” which would attach to the sperm/egg and directly affect the offspring. This was based on random genetic variation followed by natural selection though.

These ideas were largely ignored until the 1950s when plant geneticist RA Brink showed that crossing a dark form of maize with a mottled form seemed to render the dark alleles permanently inactive- this alteration would survive for hundreds of generations which came to be known as ‘paramutation’. These experiments have been repeated across the plant world and also the animal world an can be seen with mice who were fed a toxic ingredient of plastic- Bisphenol A- which resulted in the adverse effects appearing in offspring and future generations including obesity, diabetes, an increased risk of cancer, even yellow fur instead of brown. Furthermore, it has been claimed that mice who have been born from fathers who were trained to be afraid of a certain scent would show the same trait of avoidance of this same scent, though this is yet to be fully understood in terms of molecular mechanisms.

It is well known in humans that maternal behaviour in the stages of pregnancy, “prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) can cause adverse effects on the brain of the developing foetus and can result in a wide range of neurobehavioral deficits,” yet although this is heavily rumoured to be of epigenetic cause, there is so far limited evidence to suggest this without repeated environmental influences.

However, a 2015 study led by Rachel Yehuda of New York’s Mount Sinai hospital said of how children of holocaust survivors had an increased likelihood of developing stress disorders, attributing this to ‘Holocaust exposure’ with Yehuda commenting that the gene changes could “only” have been attributed to this, which hugely backs up Sam’s point of epigenetic inheritance.

But there’s more to go on, when talking to one of the writers of the aforementioned cited paper on Prenatal Alcohol Exposure, she commented on how, “the effects of breeding strong slaves to produce fast runners and tall, black men [gives strong evidence that] slavery is still in our genes.” When I questioned her about how producing fast runners would surely come down to selective breeding rather than epigenetics, she replied that it was, “a bit of both as stress can also alter expressions of genes,” before concluding that she, “just needs to find stuff to back it up.” This is not to say that there is no link between the two though as Yehuda’s study has given credence to this proposal.

“If stress smoking can influence epigenetics, trauma can, a form of stress,” she finalised by saying before going on to discuss the future of epigenetics such as how it can further be linked to schizophrenia. This is being backed by a study in the University of Manchester attempting to prove this by linking stressors experienced in some of the crucial development periods to the genesis or ‘programming’ of adult diseases thus evaluating placental and morphological development as well as conducting cognitive behavioural analyses in a rodent neurodevelopmental model of schizophrenia. This would link into a previous study which showed of how Dutch women who suffered from the famine in the 1942 were more likely to develop schizophrenia.

But in the study of the holocaust survivors, both the survivors and their children were found to possess chemical tags on the same gene and these tags were absent from the control group and whilst it remains a mystery how they were passed on, the team determined that the tags could not have been picked up from elsewhere. Marcus Pembrey of UCL said of how Yehuda’s paper was, “the very beginnings of a understanding of how one generation responds to the experiences of the previous generation. It’s fine-tuning the way your genes respond to the world.”

The combined effort of these studies goes to show a common theme, however, that psychological trauma can be passed on as an add on to genes and that Sam in effect was right. Whilst many things have been passed on by the horrors of the slave trade, another side effect clings onto the embers of humanity as a reminder of the darkest days and a past that can’t be overlooked no matter how much history tries. Slavery is truly a part of the black struggle, in more ways than just the effects it has built society on. It truly is within all of us, the inheritance of the pain of generations.