TW: Suicide

Up until the mid-20th century, traditional poetry was often at a distance from the poet’s own life, but the confessional poets began a movement of writing poems directly relating to their inner nature and experiences. Emerging in the late 1950s and early 1960s at a time when mental health was still stigmatised and swept under the rug, confessional poetry became well-known for being written in the first person, focusing on the ‘I’ and the self. This allowed the confessional poets to deeply explore their psychological nature, which included struggles with their identity, relationships with family, and mental illness. In the shadow of the horrific aftermath of World War II, confessional poetry birthed an expression of the tumults that the twentieth century had brought upon the world.

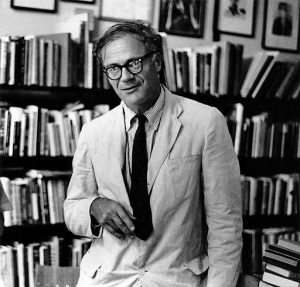

The American poet Robert Lowell has been thought by many to have begun the movement of confessional poetry. Although published collections in the 1940s had already established him as a poet, including his appointment as the US Poet Laureate from 1947-48, the publication of Life Studies in 1959 quickly became Lowell’s most influential work. The collection was already unusual in including an autobiographical prose section, ‘91 Revere Street,’ in the middle of the book. However, it was the last section of the book subtitled ‘Life Studies’ which gained widespread critical acclaim. These poems captured Lowell’s feelings about his family and his own mental state with a deeply personal touch. A marked departure from Lowell’s usual style of poetry, Life Studies was mostly written in free verse with loose rhyme and metre, and reflected the honest, open subject matter of his poems. One of the most personal poems in the collection is ‘Waking in the Blue,’ Lowell’s meditation on his stay at McLean hospital in Massachusetts, where he was being treated for bipolar disorder. His portraits of the older patients at the hospital reflect Lowell’s anxiety of becoming just like them as he ages, the poem culminating in the haunting lines, ‘We are all old-timers, / each of us holds a locked razor.’ The last poem in Life Studies, ‘Skunk Hour,’ also depicts Lowell’s reflections on his mental state. He writes, ‘I hear / my ill-spirit sob in each blood cell, / as if my hand were at its throat. . .’ The critic M. L. Rosenthal was thought to have coined the term ‘confessional poetry’ in his review of Life Studies, noting how ‘Lowell seems to regard [poetry] as soul’s therapy’ and that ‘The use of poetry for the most naked kind of confession grows apace in our day.’ Indeed, Life Studies heralded the beginnings of the ‘confessional poetry’ movement as more American poets began to write their personal experiences into poetry.

One of these poets was Sylvia Plath, who was inspired to write in the ‘confessional’ style after taking a course of Lowell’s at Boston University. Like Lowell, Plath struggled with her mental health and also stayed at McLean hospital. After many suicide attempts throughout her life, Plath’s suicide in 1963 resulted in her death at only thirty years old. Her poetry collection Ariel was published posthumously in 1965. In one of the poems ‘Lady Lazarus’, Plath reflects upon her suicide attempts through making an ironic reference to Lazarus, who was raised from the dead by Jesus. In the poem, Plath combines her experience as a woman with her struggles with her mental health. She writes, ‘I may be skin and bone, / Nevertheless, I am the same, identical woman.’ In the final stanza of the poem, Plath imagines herself as a phoenix, a mythical bird which remains immortal through rebirthing itself: ‘Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air.’

Another famous confessional poet is Anne Sexton, who was a friend of Sylvia Plath and also attended Lowell’s course. She fell into postpartum depression after the birth of her first daughter and spent many years in therapy with Dr Martin Orne, who encouraged her to write poetry. She was also mentored by fellow confessional poet W. D. Snodgrass. In her poetry, Sexton writes about her struggles with depression and bipolar disorder, her strained relationships with her family members and the realities of the female body. In ‘The Double Image,’ Sexton explores the impact of her struggles with her mental health on her relationships with her mother and daughters. She writes, ‘I, who was never quite sure / about being a girl, needed another / life, another image to remind me.’ In ‘The Operation,’ Sexton links her an operation she goes through to remove an ovarian cyst with her mother’s slow death from cancer. Once the operation is complete, she thinks, ‘God knows / I thought I’d die—but here I am, / recalling mother, the sound of her / good morning, the odor of orange and jam.’

I believe that the confessional poets were key figures in breaking down the stigmas around mental health. Through portraying their struggles with mental illness in their poetry, they proved that these topics could be openly discussed. Although understanding of mental health still has a long way to go, the confessional poets were a crucial stepping-stone in this journey.