To many people, Mary Wollstonecraft is merely a name to remember for GCSE History when learning about the Suffrage movement of the late-19th and early-20th Century. She is known for the publication of Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), and as a result for starting the discussion on gender equality. But she was so much more than just an author. She was, and is, an icon.

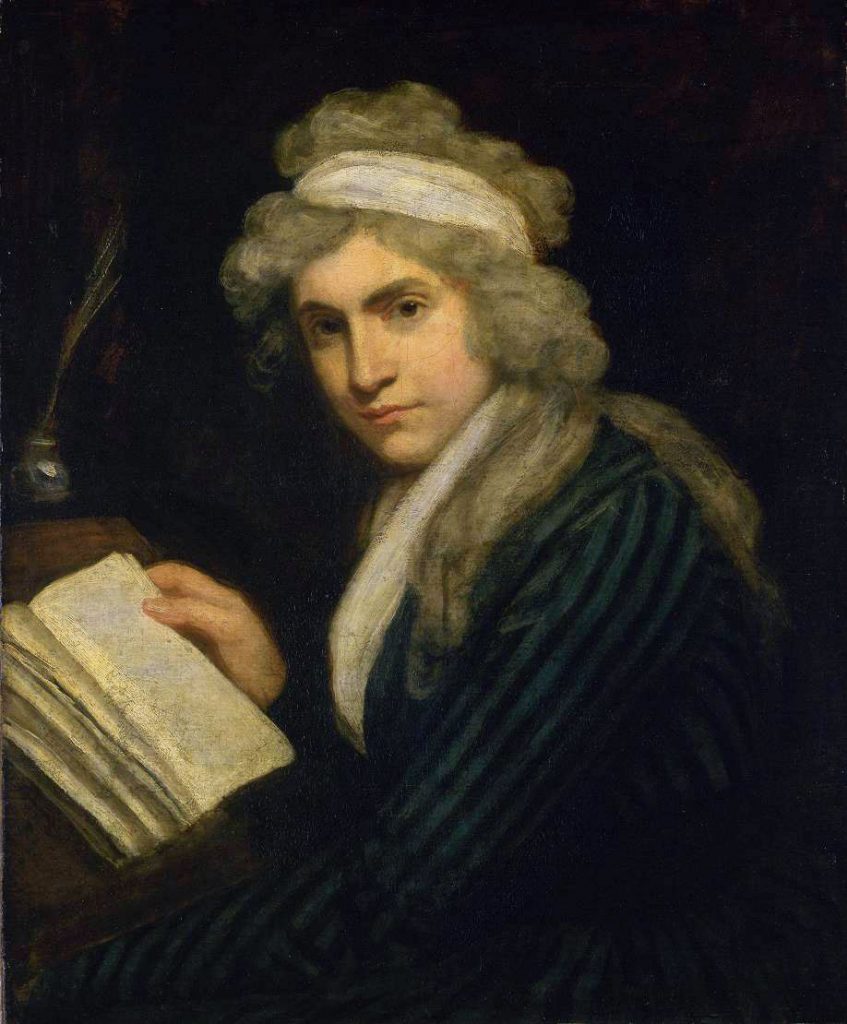

Painting of Mary Wollstonecraft (image available on Wikipedia)

In 1759, Wollstonecraft was born into abject poverty. She was not able to gain a meaningful education due to her family’s social position and played a maternal role to her two younger sisters as a result of her father’s violent nature and mother’s postpartum depression. Mary relied heavily on Jane Arden, a friend of hers; together they would read and attend lectures, both of which helped to further the minimal education to which a young Wollstonecraft had access.

Wollstonecraft had almost an innate desire to challenge social norms, convincing her sister in 1784 to flee home and try to rebuild her life, flying in the face of the traditional ideals that women would stay in their parental home until they were married. Nowhere was this more evident than in her Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), a rebuttal to the ideas put forth by Edmund Burke in his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

Edmund Burke (image available on Wikimedia Commons)

In this, Burke had stood in support of constitutional monarchy and the role that the aristocracy played in society, essentially standing in favour of embedded social and cultural inequality. Wollstonecraft vehemently opposed this position, instead arguing that Burke’s ideals promoted nothing but social stagnation. In contrast, Wollstonecraft valued progress. She correctly asserted that Burke’s world based around tradition would further entrench inequality, whether it be in terms of gender or slavery, simply because our ancestors did the same. We are yet to see a world without constitutional monarchy, especially in Europe, and we are also yet to see true gender equality or the end to slavery: Wollstonecraft would be appalled to know that her visions had been realised.

The mention of slavery in Wollstonecraft’s destruction of Burke’s outdated opinions is notable. She was amongst the first to stand in opposition to both the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade and slavery more widely. This added another layer to her admirable socio-political position and further indicates why she holds such a revered place in history.

In Vindication of the Rights of Women, she argued for all people, no matter their ethnicity, to “be allowed their birthright – liberty.” Here, she proved the importance of intersectional feminism; women could not achieve true equality until all women, no matter of social standing, ethnicity, religion and so on, were equal – a lesson which we are yet to learn today.

She had travelled to France after the publication of Rights of Men (1790) due to the uproar that the piece

The French Revolution was both a positive and negative influence on Wollstonecraft (image available on Wikipedia)

had caused, after all this was a time in which women were to be seen and not heard. She arrived in the height of the French Revolution which, as one can imagine, greatly suited Wollstonecraft. Staying true to herself, she found inspiration in the republican aims of the rebels, even if she was not greatly fond of their actions, writing “I cannot yet give up the hope, that a fairer day is dawning on Europe”. She agreed with the principle of revolt, as expected, but disagreed with rebellion purely as a means of commerce, or as a way to try and improve an economy which was built on injustice and inequality.

She returned to England after it became clear that the Jacobins were not going to grant gender equality in any guise, referring to Rousseau’s philosophy that women were to be nothing but helpers to men. She did return to Paris in 1794, however, foreseeing the downfall of the Jacobins which may result in a free press, a concept which seemed alien to 18th Century Europeans and was certainly nowhere near being achieved in her native Britain. Nonetheless, she remained a thorn in the side of Edmund Burke, denouncing his basic and traditionally propagandistic view of the Revolution; he saw Marie-Antoinette as nothing but a poor defenceless women, despite her being one of the most powerful figures on the Continent at the time.

All of this shows that Wollstonecraft was one of the first truly ‘modern’ women, at least in a 21st Century sense. As the first real ‘feminist’, advocating a utopia in which people of all genders are equal, she was truly the forerunner for debates which still occur today. Ideas which seemed radical at the time are today simply a basis for further debate. For example, in her ground-breaking 1792 work Vindication of the Rights of Women, she wrote “I do not wish them [women] to have power over men; but over themselves”. Modern-day feminists still aspire for this aim to be achieved, despite what some in the media may think, so for Wollstonecraft to have advocated this 228 years ago just goes to show how extraordinary she really was.

Mary Wollstonecraft was nothing if not individual. However, as is the case for so many brilliant minds, it was this uniqueness which ultimately plagued her thoughts. Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1798) was written by Wollstonecraft’s widower, William Godwin (who is in himself notable for being a founding advocate of anarchism) and showed the torment which Wollstonecraft’s own mind had caused her. It was a blunt but honest account of her life, which spoke of her close ‘friendship’ with a woman, her love affairs, her illegitimate child, her suicide attempts and her agonising death.

Mary Shelley, Wollstonecraft’s daughter (image available on Wikipedia)

When it came to publishing said memoir, Godwin was keen to leave in all explicit details of her life, which, in my opinion at least, is the way Mary would have wanted it to be written.

This article of course does not do justice to Mary Wollstonecraft, because how could it? She was a feminist, an abolitionist, a hugely talented writer, but more than all of that, she was unafraid. She did not care what society though of her. She had a very strong sense of right and wrong, and although at the time it may have been too radical a proposition, she certainly paved the way for the next 200 years of the fight for social equality. On top of all of this, she was also the mother of Mary Shelley, the author of Frankenstein – just in case her own legacy was not impressive enough!

She is an inspiration who deserves to be more than simply a reference in History textbooks, and so whilst I may never truly convey the power she held and the influence she has had on our society, hopefully I have managed to give a glimpse into just what a genius Mary Wollstonecraft was.