Celeste is a game about conquering a mountain by Matt Makes Games and friends. It has tight controls, hard but satisfying levels, and a story that elevates both these things.

You play as Madeline – a distinctive red-head who’s decided she needs to climb Celeste Mountain. Yet, quite soon into her journey she realises thing aren’t exactly as they seem. A mirror version of herself appears, torments her, chases her and tries to stop her from climbing the mountain.

This is all set to a wonderful soundtrack by Lena Raine. Between scenes, the music can go from quiet and reflective to pumping with an amazing beat. A personal favourite for me is “Confronting Myself”, which stirs into a cacophony of brilliance through its blend of choral pulsations and synth whirlwinds.

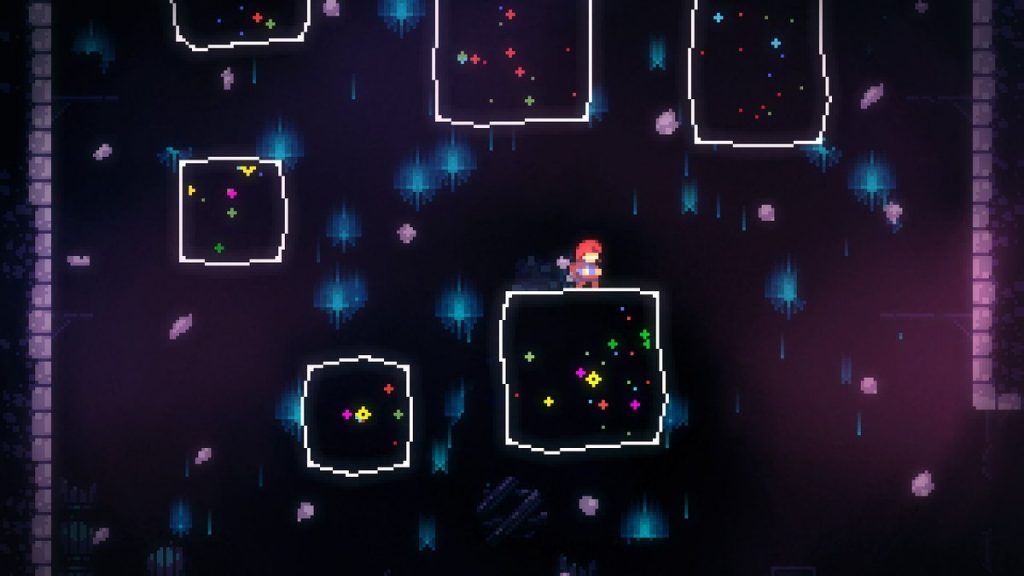

The art direction also brings to life the game. It is in a pixel art style and uses rich, vivid colours which bring out the beauty of the mountain. These are interspersed with cartoon drawings which add a sense of personality to the sprites during dialogue and key moments.

The movement in Celeste is a simple move-set which stays the same throughout most of the game. Run, jump, dash and climb.

The dash handles most of your extended mobility. It works in eight directions and acts as a de facto second jump in most situations. This means you can do difficult platforming and can lead to some impressive stunts.

The only other mechanic to learn is the wall grab. This allows you to climb upwards but has a stamina meter. Most movement, then, is dependent on quick, in the moment execution.

The move-set feels good, it acts like you think it should.

The simple mechanics means there isn’t ever an overwhelming number of things to learn. Which is great because in Celeste you die. A lot.

The variety comes with the addition of different environmental mechanics. Each mechanic changes the way in which you utilise your basic move-set. Even if new obstacles are hardly explained, you aren’t ever left confused for long.

In an early level, there are large blocks of dark matter, that, if you dash through, pull you all the way to the other side. Once you see them, you can tell that they are something new and distinct. I knew straight away that I should try dashing through them.

These environment challenges escalate through each level until they are making you pull off ridiculous stunts with them. This presents a difficulty curve that doesn’t feel like it’s treating you unfairly.

Many screens I played consisted of constant death but this never felt like a burden. You get respawned at the start of a screen when you die, stopping unnecessary frustration. This leads into a loop of death and learning. All until you execute every single movement exactly right and beat the screen. And this feels amazing.

The only gameplay I didn’t really enjoy were the feather breathing segments. I feel like they worked thematically, but were too far from the central mechanics to feel right.

As well as the main route, Celeste has strawberries littered throughout its levels which get increasingly difficult to pick up. For a challenge, you can also attempt the B-Side stages, remixing the original levels in cruel and finger-hurting ways.

These were all things I might expect from a good platformer.

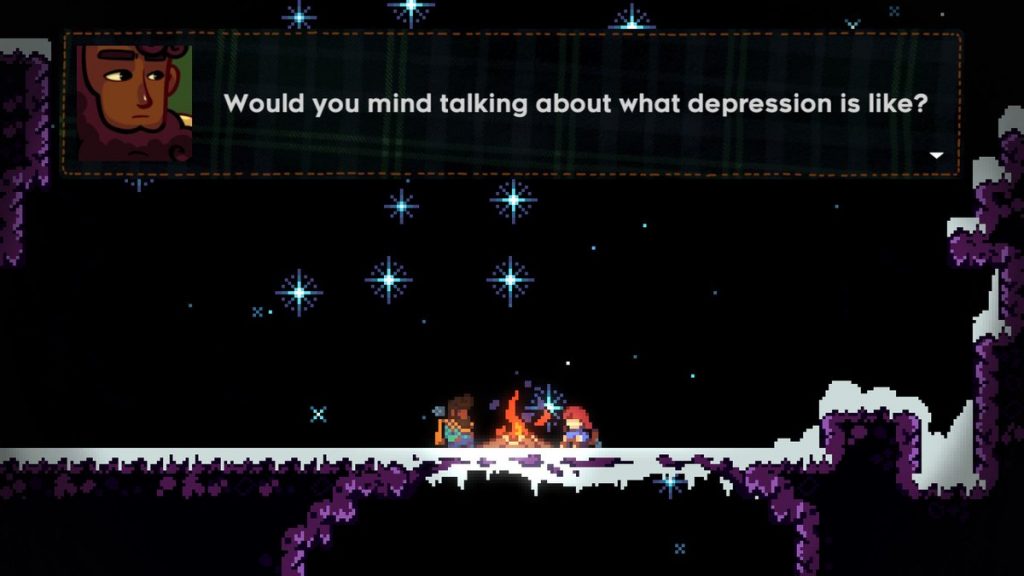

What I didn’t expect was how honest Celeste was about its subject matter. The game is about depression, and the writing makes this totally clear. Madeline talks frankly about the struggles she faces and how depression has affected her – more games could stand to be this open.

At one point, Theo (a fellow climber) asks Madeline, “Would you mind talking about what depression is like?” This comes at a quiet moment in the game where there is no platforming. No frustrating challenges to beat. Just an honest talk between two friends. These are the moments which make Celeste so special.

You could imagine the game as the pure platformer it might have been. Madeline could have been an empty avatar which you use to progress from screen to screen. The games still would be great, but something would be missing.

The emotive narrative elevates Celeste to a whole new level. Without Madeline, Theo or any of the other characters Celeste would not be the same game.

Celeste shows that compromise is not always needed in platformers. Its story and mechanics work hand in hand to deliver an experience that is both compelling and great to play. In this sense, Madeline becomes the perfect conduit between the gameplay and the player. Every cliff she climbs, every struggle she faces, every death she dies; it’s all yours too.