It’s been almost two years since protests broke out in Hong Kong following the introduction of an extradition bill by the country’s Sinophile Chief Executive, Carrie Lam. The bill aimed to amend the so-called Fugitive Offenders Ordinance, allowing the transfer and detainment of suspects to be tried under the judicial system of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). A series of peaceful protests against the amendments first occurred in May 2019 when the bill was proposed, and grew to marches of nearly two million people by August of that year. However, after the government repeatedly refused to revoke the bill, violence broke out between protestors and the police. Although the bill was eventually discarded in September 2019, there has been ongoing social unrest to fight for the city’s democracy ever since.

Hong Kong is a city-state that, although geographically affixed to mainland China, is run according to a different legal system. Since the British handed over its former colony to the PRC in 1997, it has been classified as a ‘Special Administrative Region’ of China, heralding a “one country, two systems” policy. Many argue that the proposed bill threatened this established principle as well as Hong Kong’s freedom of assembly and speech; the very democratic liberties that ensure its autonomy from China.

Rising tensions between citizens and the government quickly escalated during the second half of 2019 and protestors caused massive disruption across the city, blocking roads and even storming government buildings. Many voiced their anger towards what they regarded as an abuse of power by police in their overly aggressive response to the protests.

Beijing reacted strongly by imposing a new National Security Law (NSL) in Hong Kong, with the purported aim of reducing social and political instability in the region. This piece of legislation was enacted on 30th June 2020 – symbolically, just one day before the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover to China. Some key provisions in the NSL include: the establishment of a new security office with its own Chinese law enforcement team; the precedence of Chinese law over Hong Kong law; and restriction of the constitutional power of the judiciary. The law also criminalises “collusion with foreign forces” and “subversion” against the PRC government in Beijing, making such crimes punishable by the maximum sentence of life imprisonment for both permanent and temporary residents of Hong Kong.

Following the rapid enactment of the legislation, Chief Executive Carrie Lam said that the law would not be retroactive nor undermine Hong Kong’s independent judiciary system. However, with tighter regulations and increasing uncertainty over what actions might be considered “subversive” or “collusive” by Beijing, many of the city’s inhabitants believe that their basic human rights have been harmed by this discriminatory encroachment of the law. The hurried introduction of the NSL sparked yet more public outrage and heightened tensions within the city, with protestors particularly enraged by the erosion of Hong Kong’s judicial independence and autonomous status.

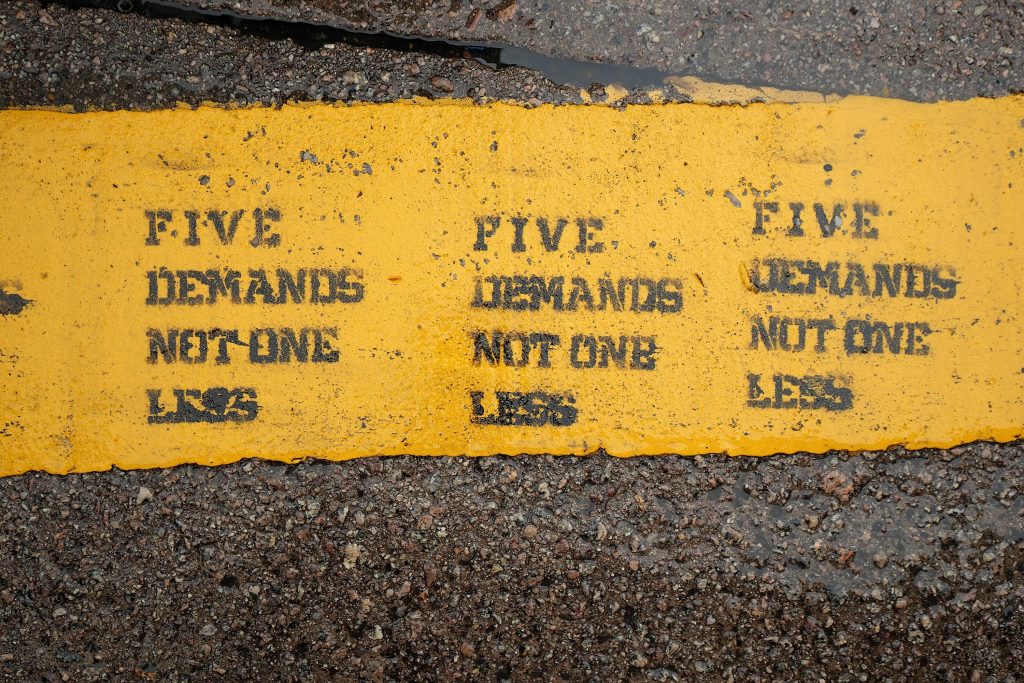

Protestors didn’t have to wait long to find out just how restrictive the NSL was to their freedoms. Shortly after the legislation was enacted, the government declared that even political slogans, such as “Five demands, not one less” and “Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our times”, constitute subversive acts that endanger national security, and so could result in criminal charges being brought against anyone found in possession of placards or stickers displaying them as well as against anyone heard chanting them in the streets.

One of protestors’ most popular slogans, now carrying a prison sentence under the NSL (Source: Etan Liam on Flickr)

That’s not all, though, as the NSL doesn’t only affect Hong Kong’s permanent residents. Many fear that the city’s status as a leading international hub may suffer, too, as it is reduced to simply another nondescript Chinese city. Indeed, the New York Times, has already decided to relocate a major part of its office along with a third of its Hong Kong-based staff to South Korea as a result of their concerns over the loss of press freedoms they previously enjoyed in the city.

What the slogans also signify, however, is that the city’s anger over the PRC’s perceived infiltration of Hong Kong is undiminished and that the city’s pro-democracy movement remains strong. Although it is still to be seen whether Hong Kong’s citizens have the collective power to overcome China’s suffocating grip on their legal system in 2021, the movement’s message remains steadfast: the city’s unity will never be compromised by Beijing’s political interference.

Image: Studio Incendo on Flickr