Chemicals compose everything, including items that we are entirely dependent on, such as plastics and antibiotics to name a couple. Nonetheless there remains a sense of chemophobia – the fear of chemicals that is ultimately driven by generalisations of a few unsafe compounds. Here lies the conflict between our reliance on particular items and the impact they have on our own vitality, and the health of the environment. How do we know what chemicals are polluting our bodies and what can we do about it?

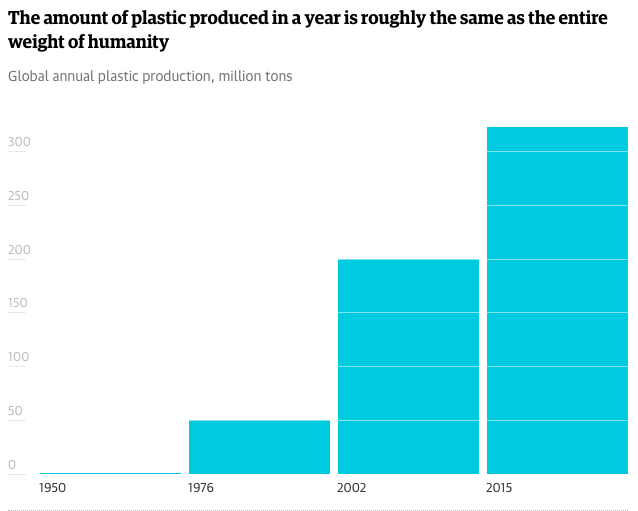

Plastics are foundational to our present human societies and their production has increased every day to meet new demands (figure 1). It can therefore be challenging to begin to decipher if any of the thousands of products we consume and ingest are polluting us in a harmful way.

Plastic migration is the process by which chemicals are transferred onto food items at trace level, occurring upon contact with some plastic containers. It appears that the migration of chemicals increases when food is heated in plastic and when the food stuff is particularly salty, acidic and fatty.

Figure 2. While BPA can be indicated by the number 7 on plastic containers, there are other chemicals that fall under this category.

There are also a number of studies into the chemical Bisphenol A (BPA) which can sometimes be identified by a marking of the number 7 on the bottom of a plastic container (Figure 2). BPA is an industrial chemical that is used in the production of some plastics, found for example on the insides of cans and on till receipts. It is ingested by humans through skin contact and some research has suggested that acidic foods such as sodas more readily absorb BPA. Studies have shown that BPA’s chemical structure is similar to that of oestrogen, resulting in it acting as an endocrine disruptor in both sexes even at the parts-per-trillion level, by changing the expression of oestrogen-responsive genes and hormone regulation. Phthalates contained within polyvinyl chloride (PVC) products (marked with an embossed number 3 on packaging) are also thought to have a similar effect on the human endocrine function whilst also releasing dioxin (a known carcinogen) into the atmosphere during production.

So what can we do? From a top-down level it may be preferable to follow France’s ban on the use of BPA in packaging, utensils and containers that are intended to come into contact with food. Encouraging companies to stop using BPA and PVC in their production lines or at the very least labeling their products is another way in which we might envisage change. Individually, some people suggest opting for glass or cardboard containers of food and drink instead of cans as well as reducing consumption of single-use plastics.

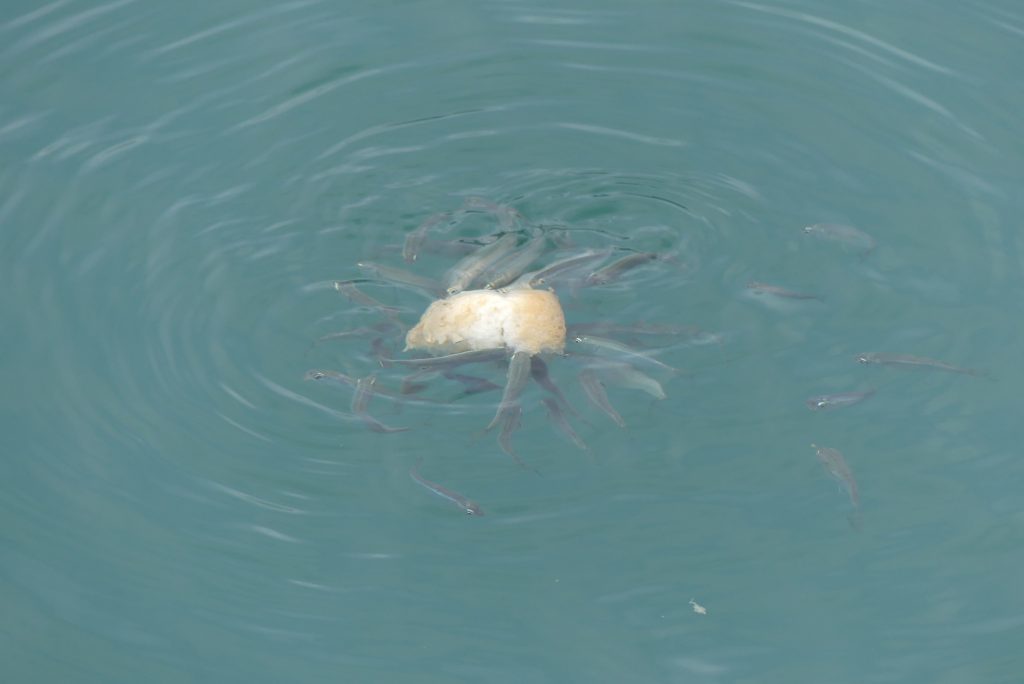

The stories of microplastics in the oceans and freshwater systems have recently gained gravity in the news, with shocking findings of around 10,000 plastic pieces in a litre bottles of water, two times as much as found in tap water. It is thought that many of these pieces originate from synthetic clothing that release around 2000 plastic fibres each time they’re washed (Vince, 2014). Although wastewater systems tend to remove around half of this, it has been proposed that the proportion could be increased by slowing down the flow of water through such plants, simultaneously increasing the costs.

However, it is not only in water that plastics are present, anything made with that water, such as bread, soup and formula milk for babies will contain them too. Additionally, plastic binds to toxins in water, which, when ingested by humans directly, or indirectly through shellfish for example, present a profound health risk. It is therefore hard to determine whether it is the plastic itself or the toxins that has the capacity to damage our health

But how dangerous are microplastics for human health? No one really knows for humans at least, particularly in the long term. This is a challenging idea to grasp given the number of decades we have been using plastics increasingly prolifically for. We do however know the adverse effects of microplastics on other animals, such as fish, and so to imagine that we would be affected to some extent seems very plausible.

Ultimately, there are so many sources of synthetic chemicals in our bodies that makes pinpointing the cause of health issues challenging and overwhelming. Perhaps, therefore we should continue to question how comfortable we are with not fully understanding the influence of the products we use on our health and seek to better understand the impact they have on our bodies

To view a simulation which illustrates the movement of plastic point-source pollution in the oceans, click here.