Image caption translates as “The biggest collection of drawings, prints and sculptures by Käthe Kollwitz in the world.”Image of a current museum document Image: Writer’s own

The vibrant city of Cologne in northwest Germany is renowned for its dramatic cathedral, its picturesque Christmas markets and for all things proudly labelled “Kölsch”, including the city’s own dialect and its popular range of beers. However, not to be overlooked are its numerous museums and galleries. Alongside such attractions as the huge Museum Ludwig and the impressive Römisch-Germanisches Museum – both situated in the very centre of town in the shadow of the Kölner Dom – are a great number of small galleries, many of which are solely dedicated to individual and, often, local artists. On a recommendation from a friend, I visited the Käthe Kollwitz Museum in Neumarkt. The relatively small gallery is discreetly located on the top floor of a small shopping centre and is very modest in its layout and design: its simple black and white palette and slightly harsh, confined atmosphere poses as an unobtrusive mirror of Kollwitz’s own work. Her drawings and prints line the walls, bordering the selection of sculptures that dot the exhibition space. The gallery feels almost claustrophobic: its small size compounded not only by the low, exposed ceilings but also by the unyielding intensity of the artwork on display.

A visit to the exhibition is a lesson on Kollwitz’s life and an insight into late 19th and early 20th century Germany. Her work centres on the dark and on the tragic: on poverty, hunger, war and loss. Born in 1864, her lifetime spanned both World Wars – she died on 22nd April 1945, just days before the official end to the conflict in Europe – and, unsurprisingly, their impact is a major theme in her work. In many of her pieces on display there is an immediate and unavoidable focus on the hardship and the struggles that war forces onto the lives of the average family. Having lost the younger of her two sons just two months into the First World War, the extreme pain suffered by those who live through conflict is present in much of her work.

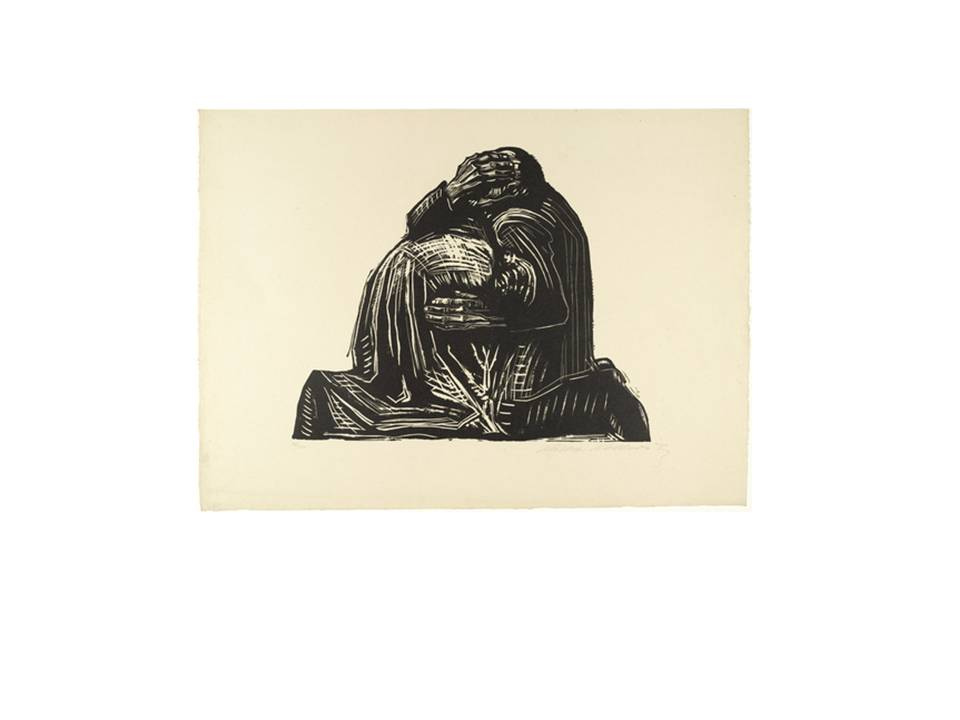

Käthe Kollwitz: Die Eltern (1922) Image: dangreen2012 on Flickr under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

The concept of a grieving family is especially evident in the woodcut series Krieg (1918–1922). Each image functions as a striking and nightmarish black and white window into early 20th century Europe. The depictions of broken mothers (Die Mütter, 1921/22), widows (Die Witwe I, 1921/2 and Die Witwe II, 1922) and the young “volunteers” accompanied by death (Die Freiwilligen, 1921/22) are uncomfortable to look at due to the pure horror that they evoke in the viewer. The debilitating anguish and grief of the subjects is expertly reproduced in the contorted bodies and tormented expressions: the simplicity of the two-tone palette and the prints’ emphases on hands and faces ensures nothing distracts from the theme of human suffering. The third image of the series, Die Eltern (1922), stands apart from the others in that the faces of its subjects are entirely hidden. Their grief is instead portrayed through their hunched, defeated bodies: the father supporting the mother in their communal agony, his hand obscuring his face. As a single, united, almost indistinguishable form, there is some comfort to be taken from the suggestion that they have one another for mutual consolation.

Children and, in particular, the concept of motherhood, span Kollwitz’s entire artwork: these were not themes approached only after the tragedy of war had struck. Her two sons were key influences. The drawings of baby Hans and of Peter as a young boy are soft and gentle: their light touch and minimal shadows are a world apart from the darkness of Krieg. As stand-alone pieces they portray youthful innocence and are images of sweetness and beauty; they become poignant, however, when viewed with the knowledge of Peter’s terrible fate. More heart-breaking still – in their own right, as well as in context – are the pieces that depict mothers with dead children. In 1908, Kollwitz’s older son, Hans, fell extremely ill with diphtheria and it is this frightening event that many claim prompted such pieces as Tod, Frau und Kind (1910). The image shows a mother, who bears an unmistakable likeness to Kollwitz, with her face pressed so close to that of an infant’s that they seem to merge into one. In contrast to the uncontrolled grief of many of her other pieces, Tod, Frau und Kind has a stillness to it that remains unshaken even after one notices the long hand by the child’s neck, presumably belonging to Death.

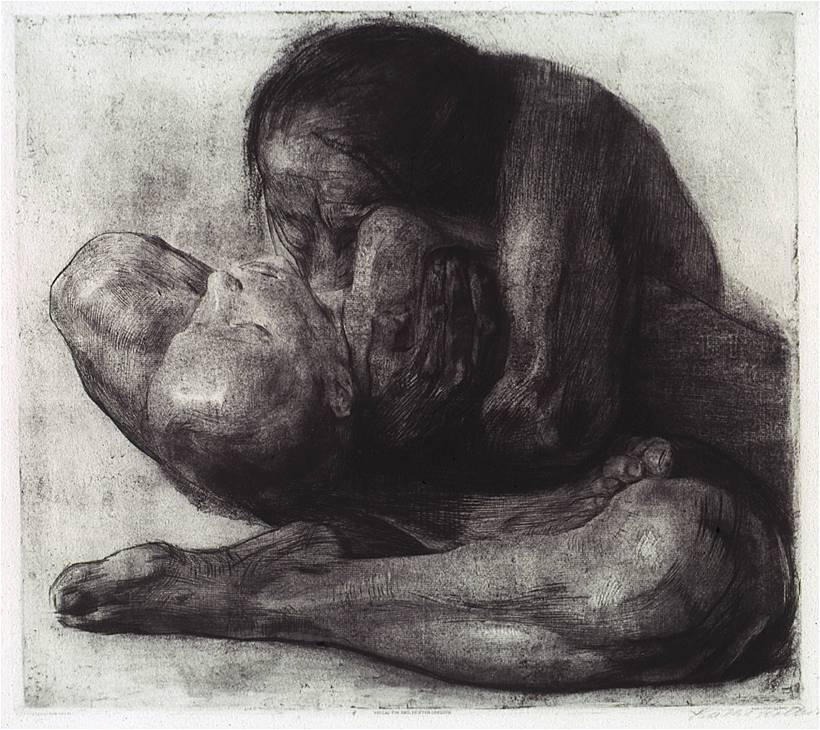

Käthe Kollwitz: Frau mit totem Kind (1903) Image: Hannah Grover on Flickr under https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Earlier still, however, Kollwitz produced artworks on the subject of child loss. Frau mit totem Kind (1903), for example, which depicts a mother clutching the body of her child in an animalistic embrace , appears to display the kind of unrestrained and frantic mourning that is the focus of many of her later projects, including a number of expressive sculptures. It is reminiscent of Die Eltern in the way that the mother’s face is concealed. However, this time, we see a hand, her feet and parts of her limbs, as her body, deformed in her sorrow, hunches over her child. It is troubling to think that this picture, representing perhaps a fear at the point of its creation, foretells what Kollwitz would experience just over ten years later.

For a small gallery, the exhibition covers a wide range of subjects. Alongside death, war and motherhood are sections on Peasants’ War, A Weavers’ Revolt, love, women and politics. There is also a collection of self-portraits. These artworks are interesting to look at because of their brutality: the drawings she made of herself, the museum explains, were not intended for public viewing and so Kollwitz felt free to be ruthless. The images represent a form of self-criticism and they therefore come across as incredibly personal and intimate. This sense of true feeling is key to Kollwitz’s appeal: her work has a rawness which penetrates and lingers with the viewer. Her images are swamped in emotion, whether implied through technique or pushed onto the viewer by means of subject matter and dramatic representation. Rarely has the dark and the tragic been so effectively explored.