Today in the twenty-first-century, art is threatened with regards to its funding. In the past, art was usually funded by a commission, and paid for by the state, via whoever embodied the state at that time – usually the king, duke or a wealthy merchant. This state commission funded some of the greatest artworks we know and still admire today.

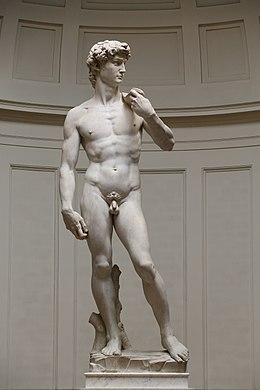

A prime example is one of the most famous and referenced pieces of sculpture in human history: David by Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni.

David was commissioned by the Florentine Government in the 16th century to adorn the rooftop of Florence Cathedral, however, as it transpired, David ended up in the Palazzo Vecchio instead; though this is still very much a direct example of state patronage of art.

Patronage is the backbone of how specific artworks, and the art world at large, are funded. As previously noted, it was mainly individuals with great power and influence who funded and commissioned pieces of art – particularly with the intention to adorn their grand palaces and to commemorate great contemporary events. However, as society became more democratic and egalitarian in nature, and the balance of power moved away from sole individuals with great wealth, power and influence to democratically elected governments the way art was funded change, even if not noticeably.

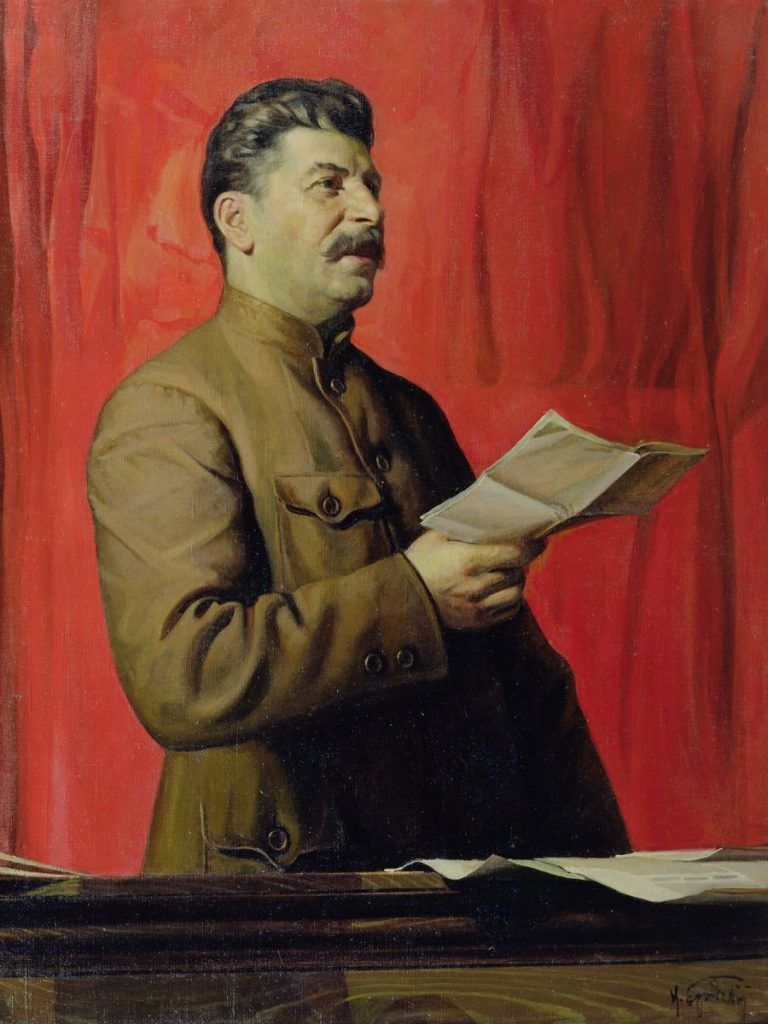

State patronage continued in a similar manner during the twentieth century, as it was the method in which the USSR, Italy under Mussolini and the Third Reich commissioned artworks. However instead of it being one king, duke or merchant, it was an all-encompassing totalitarian party made up of members. Some of the most iconic artworks, particularly sculptures of the twentieth century, were made this way.

Social realism is perhaps the most symbolic form of this state patronage illustrated most notably by sculptures and artworks within a specific time period. From 1932 to 1988 – in other words, from “Man of Steel” Stalin to the great reformer Gorbachev – it was the sole style of art permitted within the USSR.

It permeated all forms of art including sculptures, paintings, posters and architecture. The legacy left by this uniform adoption of a sole artistic style is evident within what is now Russian Federation to this day. The legacy of socialist realism is also noticeable in the former Soviet republics and eastern bloc countries which were once under the control of the USSR – whether directly or by them being satellite states of the USSR.

Within the democratic West during this time, great merchants and people of great influence and power still commissioned artworks – but a hybrid occurred. Democratic governments formed art councils and culture ministries to fund galleries and places of significant cultural value. It became common for taxpayers money to fund public art galleries and cultural venues, such as opera houses and concert halls.

This hybrid system was common until the 2008 Great Recession struck all over the world and caused great damage to the economies of developed, particularly western, nations. A consequence of this catastrophe was to implement necessary austerity measures to firstly reduce, and ultimately eliminate, the great debts accumulated in order to successfully prevent the collapse of the financial system. This meant cuts had to be found in the budgets of governments globally.

Government expenditure could not be cut in policy areas like health or defence, due to political reasons, so governments had to find ‘non-essential’ departments to cut. These were unfortunately departments that dealt primarily with cultural affairs. Particularly in the UK, austerity hit the department and non-departmental organisations responsible for cultural affairs hard. Cuts were of millions of pounds (£7.2 Million over 5 years from 2010/11 to 2015/16) and that is solely Arts Council England; other national art funding authorities had their funding cut as well.

Funding provided specifically by Arts Council England was heavily invested in the GLA (Greater London Area) rather than the rest of England. Consequently, this reduction in funding has inevitably led to the reduction in public access to art nationally and forced those who provide cultural services to find funds elsewhere instead of solely relying on grants from the government and its non-departmental organisations. Such a challenge has made those who provide cultural services to think outside traditional ways and find an effective solution.

In my home city, Birmingham, the Council transferred responsibility of the Birmingham Art Gallery and the numerous historic houses to a trust.

This trust now has ultimate control, and as it is a charitable trust, it relies on charity alone (specifically entry fees in the cases of the historic houses and trust memberships) for annual access across all sites. Birmingham has led the way in finding a new and innovative way to funding its cultural heritage, even though it pains me that the historic houses are no longer free to access.

However, a question remains: what about individual artists? Who is going to fund them? Like everything these days: the internet. A new method of funding emerged during the development and release of pay apps like Paypal and, more recently, sites like Patreon. These are primarily small donations by admirers of the artist’s work, or someone who wants a piece of art and specifically commissions the artist. This has led to a renewed growth of art production; now not in the great cities of Italy, but rather online.

The plethora of artists now online has resulted in an unfortunate era where artists are not as valued as they should be financially or socially. Commissions are usually very expensive and it has meant that being an artist has become more of a part-time hobby, rather than a full-time profession. Furthermore, there is a tendency among some to consider free exposure payment in of itself, which should not be the case especially when it is their primary career.

So in reality, even now one of the best ways for an artist to achieve fame, monetary success and wide-ranging recognition, is to have a patron of the arts, whether it be the individual artist, or a publicly funded art gallery. This patronage is not bestowed on all who deserve it and unfortunately, many artists do not get the recognition they deserve just because they don’t have the connections or they weren’t lucky. However there is hope, as the publicity the internet provides can ensure that lesser-known artists can achieve exposure and hopefully then find themselves a patron, whether state or private, to fund their artistic endeavours. Instagram posts can reach millions of people in a second and this is something we can look forward to in part.

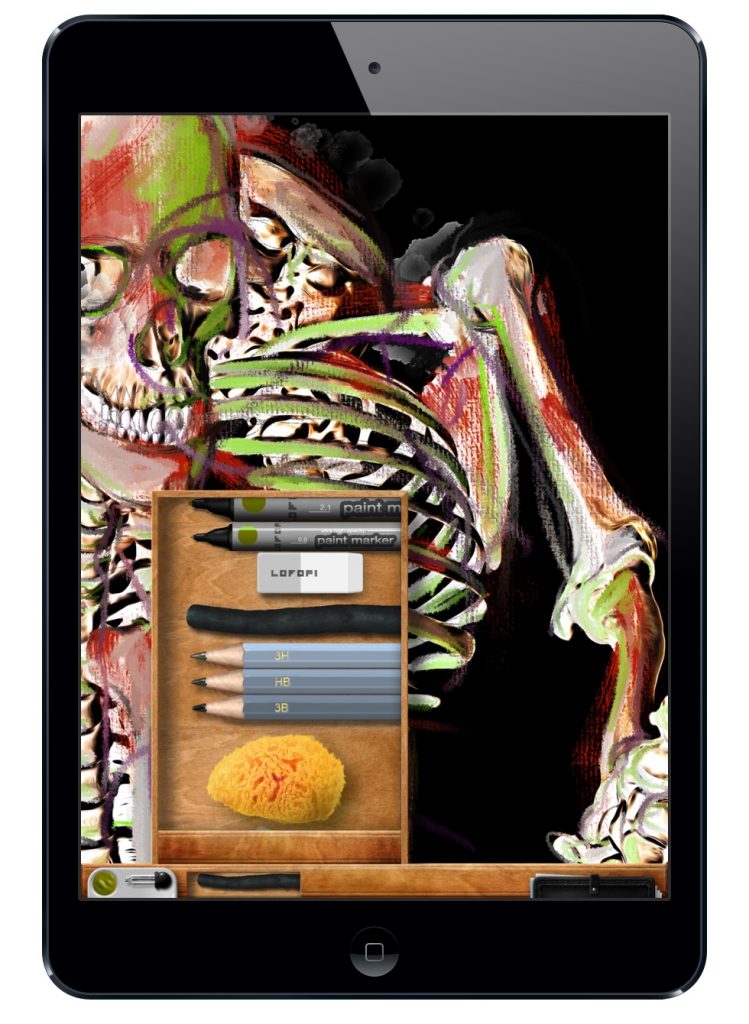

Technology has opened many doors within the art world; now art is not created only by the traditional canvas, oil paint and brush, but also the iPad.

Technology, if harnessed correctly, can also assist in supporting the arts, whether that be the individual artists themselves or a historic house. People can raise thousands of pounds via appeals on Facebook or donations on Paypal. Within the darkness raised by austerity and the commonality and under-appreciation of artists there is still light.

The future of art funding, to me at least, is a hybrid of private patronage (whether traditional or online) and the support of the state-supported art galleries. Both have a role in the development, promotion and continuation of our cultural life, however I suspect as austerity takes its toll, the former will be taking on most of the responsibility.