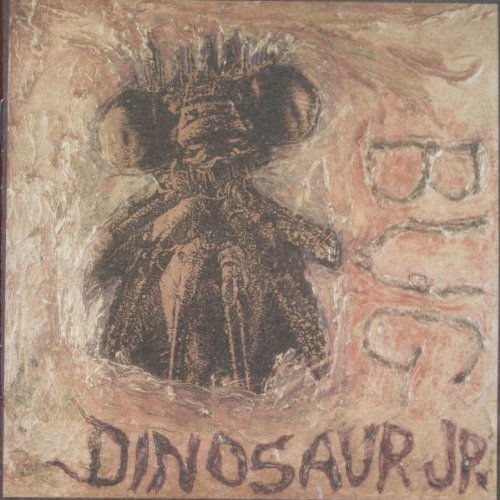

Dinosaur Jr.’s ‘Bug’

“Now, looking back on it, I’m like, ‘Jesus, we are so not normal! Nobody really played like that!’”

So recalled Lou Barlow, Dinosaur Jr.’s bassist, in 2005, and there’s a lot of truth in this statement. The bands influences are many and varied, and when mixed together these created a unique sound in the 1980s. Gerald Cosloy, college friend of lead guitarist and singer J. Mascis and head of Homestead Records (with whom Dinosaur Jr. released their first album) said of the band’s music: “It was its own bizarre hybrid… It wasn’t exactly pop, it wasn’t exactly punk rock – it was completely its own thing”.

Among the many things contributing to this alternative aural melting pot, Mascis’ vocal style has been frequently compared to that of Neil Young, employing a low-key, nasal drawl. But Mascis later commented that the comparisons “got annoying,” and cited other influences in John Fogerty, singer for Creedence Clearwater Revival, and Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones.

They were one of several classic rock artists of whom Mascis was a fan; he has also cited the Beach Boys as one, although as I write this, bassist Lou Barlow’s distorted screams (“Why don’t you like me?”) are blaring through my headphones on the track Don’t, and it’s hard to reconcile that with I Get Around. It’s more akin to hardcore punk – the sound is constantly distorted and very loud, and there’s a lot of feedback. When the manager of SST Records first heard the recording of You’re Living All Over Me, the album preceding Bug, he had to check with Mascis that this was actually how the album was meant to sound, as the level on the tape was so consistently high and distorting.

Barlow, in turn, drew heavily from his background in hardcore music, and looked up to artists such as Lemmy (Motörhead) and Johnny Ramone, who he described as his hero. And Dinosaur Jr. went on to influence the alternative rock of the 1990s, particularly in their use of contrasting quiet-loud dynamics to emphasise their use of volume; it was particularly popularised by groups such as the Pixies and Nirvana.

Some of the artists mentioned so far a world apart. Dinosaur Jr.’s “Related Artists” page on Spotify is made up of a pretty eclectic bunch, too. And the result of combining all of these elements together is suitably non-conformist. The instrumental backing is furiously energetic, in parts sounding like an angry protest. And maybe it was; Mascis ruled Dinosaur Jr. with an iron fist, dictating to Barlow and drummer Emmett Patrick “Murph” Murphy exactly how they should play their parts. In 1989, a year after Bug’s release, tension between Mascis and Barlow escalated, resulting in Barlow being kicked out of the band. On his 1991 track The Freed Pig, Barlow (with his new band, Sebadoh) attacks Mascis for the way he was treated in Dinsoaur Jr.:

Self-righteous and rude,

I guess I lost that cool,

Tapping ‘til I drive you insane.

But in spite of this, Mascis’ voice is incredibly laid back and detached. Michael Azerrad, in his 2001 book Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes from the American Indie Underground, 1981–1991, described Mascis as “removed from the feelings he was conveying in the music.” At times, he sounds almost bored.

Listening to this album, you never quite know where you are. The opener, Freak Scene, to some extent foreshadows Nirvana’s Feels Like Teen Spirit, which would follow three years later. Music journalist Everett True credited the track with “invent[ing] the slacker generation.” The track is rated among the best of the band’s songs; in particular, Mascis’ guitar playing is exceptional. According to True, he plays “effortlessly and fully in control”; Tom Maginnis (AllMusic) says that “Mascis is one of those rare guitarists who seems to have the ability to voice emotion while soloing.”

But other tracks from the album, including the song that immediately follows, No Bones, are far grittier in nature, perhaps making them somehow less accessible; although that didn’t stop the album from topping the UK Indie Chart, making it the band’s first major success outside the USA.

I’m not always convinced by the combination of styles with which I’m presented when listening to Bug, but it’s still a solid album overall. The only thing consistent throughout is its unpredictability. If it’s impossible to hear the Beach Boys in Don’t, the final track of the original release, it’s more than evident on the bonus Keep the Glove from the 2005 reissue.

The playlist I’ve formed from listening to 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die now comprises 7 hours of music, including 4 tracks from Bug. You can listen to it here.